In 1940, Nazi armies reached Turkey's Balkan borders. The Nazis enacted similar anti-Semitic laws in their ally Romania, as they did in Poland. By 1941, when 4 thousand Jews were murdered by the Nazis in Iasi, Romania, Romanian Jews had no choice but to go to Palestine. A large group of rich and intellectual Jews rented a transatlantic cruise ship called Queen Mary, which they saw in the advertisements in the press, from the Greek agency called Campania Mediteranea de Vapores Limitada, with the money they collected to escape to Palestine using Turkish territorial waters, but instead a wooden ship called Struma with a capacity of 100 people was allocated,. To calm the Jews who realized that they had been deceived, the agency said that the ship that would take them was waiting outside Romanian territorial waters.

In 1940, Nazi armies reached Turkey's Balkan borders. The Nazis enacted similar anti-Semitic laws in their ally Romania, as they did in Poland. By 1941, when 4 thousand Jews were murdered by the Nazis in Iasi, Romania, Romanian Jews had no choice but to go to Palestine. A large group of rich and intellectual Jews rented a transatlantic cruise ship called Queen Mary, which they saw in the advertisements in the press, from the Greek agency called Campania Mediteranea de Vapores Limitada, with the money they collected to escape to Palestine using Turkish territorial waters, but instead a wooden ship called Struma with a capacity of 100 people was allocated,. To calm the Jews who realized that they had been deceived, the agency said that the ship that would take them was waiting outside Romanian territorial waters.

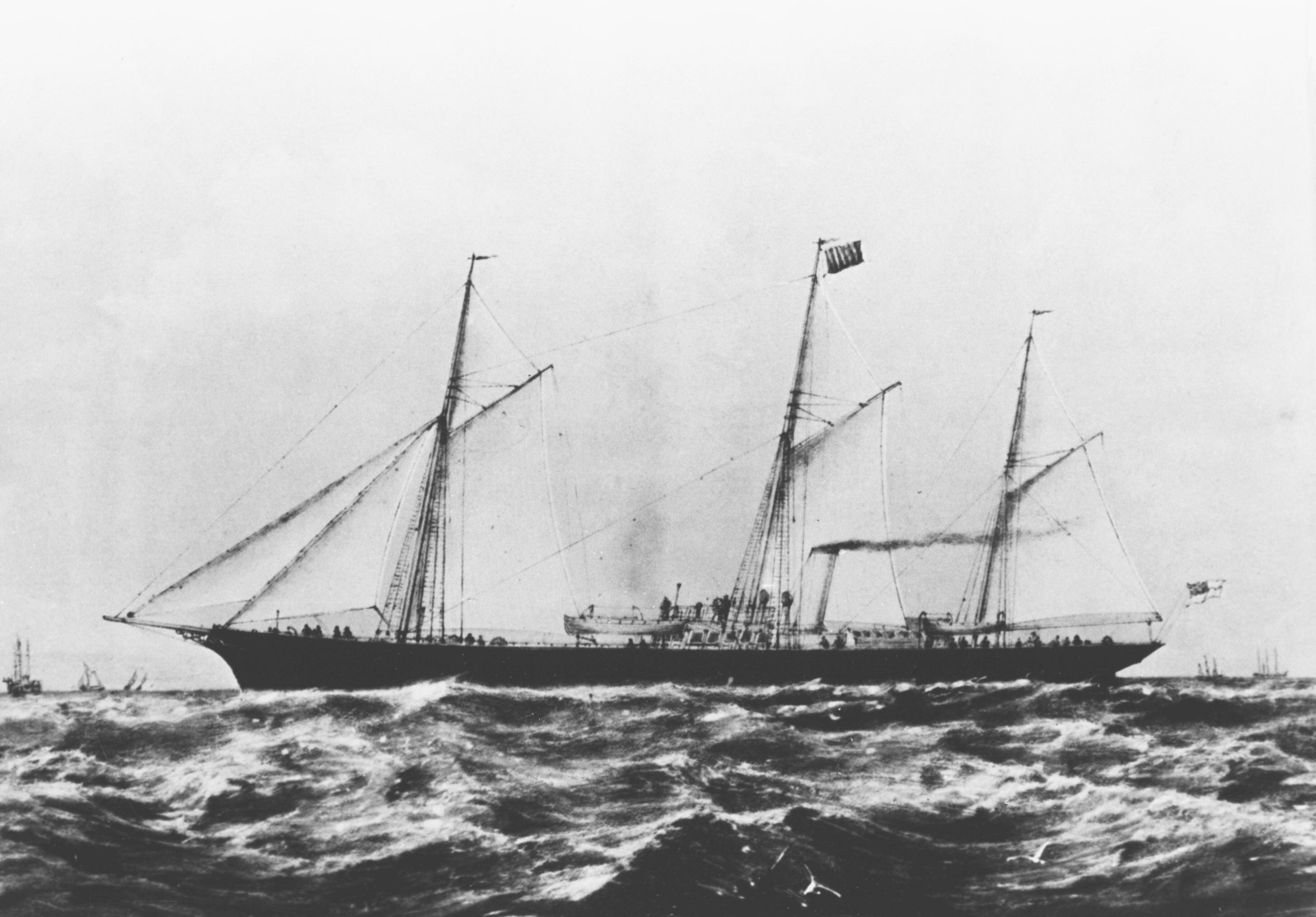

Struma was a 46 meter long, Panama-flagged Bulgarian coal ship with an 1830 model engine. It was built in 1867 at a shipyard in Newcastle, England, and had a capacity of 100 passengers. It was deployed in the Balkan Wars and was used for animal transportation after the war.[3]

With the approval of the pro-Nazi Ion Antonescu administration in Romania, Struma left the port of Constanta on 12 December 1941 with a total of 791 passengers (note: according to some sources, the number of passengers was 764) and 10 crew. The passengers were told that they would be given immigrant visas to stop in Istanbul and go to Palestine. Passengers were allowed only 20 kg of luggage, and customs officers confiscated many of their valuables and even food. People had to sleep in piles of fish in the cabins below deck, each of which was reserved for between 40 and 120 passengers.

Since it had an engine failure during departure, it could only be towed from the port to the open sea by tugboat. Because the coast of Constanta port was mined, he was taken out of the mined area accompanied by a Romanian ship. Then, throughout the night, the ship drifted at sea and broadcast a distress call as the crew tried to repair the engine. The next day, the Romanian tugboat came upon these calls and stated that they could only repair the engine for a fee. Thereupon, the refugees, who had no money left, gave their wedding rings to the tugboat staff. Thus, Struma was able to continue the journey, but when it broke down again two days later, on December 15, it could only reach Istanbul by towing and had to anchor off Sarayburnu.

Thereupon, negotiations began between Turkish officials and British diplomats about the future of the refugees. Since the British government wanted to minimize Jewish immigration from Europe to this region due to the increasing tensions between Arabs and Jews in Palestine, British diplomats were requesting the government of Refik Saydam not to allow the Struma ship to continue on its way. Meanwhile, Germany's consul general in Istanbul reported that there was an epidemic on the ship, and Germany put pressure on Turkey not to disembark the passengers. This passage out was already closed with the decree no. 2/9498, issued in August 1938, stating that "Jews, who are subjected to pressures in terms of living and traveling on the state land of which they are citizens, are prohibited from entering and residing in Turkey, regardless of their current religion..." Additionally, Romania did not accept the ship being sent back to them. Meanwhile, food stocks on the Struma ship were rapidly decreasing. Those on the ship could only drink soup twice a week and eat only some peanuts and one orange every day, and the children could be given some milk in the evenings.

After weeks of negotiations, the British government allowed several travelers with expired Palestinian visas to travel to Palestine. Martin Segal and his family were also taken off the ship upon the request of the USA, through Vehbi Koç's intermediary efforts and the Turkish government's efforts. Martin Segal is the Romanian manager of a US oil company called Standard Oil Company of New York, and Vehbi Koç is the Turkish representative of the same company, and had held a series of meetings with the Minister of Internal Affairs Faik Öztrak and Istanbul Police Chief İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil for the Segal family. Additionally, a woman named Madeea Solomonovici had a miscarriage and was taken to Balat Or-Ahayim hospital in Istanbul. Thus, a total of 9 passengers were able to disembark, leaving 782 passengers and 10 crew members on board.

Aid supplies were delivered to the ship, which was anchored off the coast for 9 weeks, by the Red Crescent and the Jewish community in Istanbul. The aid was organized by Simon Brod and Rifat Karako, leaders of the Jewish community in Istanbul. Struma's faulty engine was also dismantled for repair.

When negotiations between Britain and Turkey regarding the fate of the passengers on the ship reached an impasse, the Turkish government took action to take the ship out of Turkey's borders on February 23, 1942. First, a small group of police tried to board the ship, but the refugees did not allow it. Then, a police force of approximately 80 people surrounded Struma with motor boats and managed to board the ship after a resistance that lasted about half an hour. The ship was anchored, tied to a tugboat, and towed to the Bosphorus and from there to the Black Sea. As the ship was forcibly withdrawn from the Bosphorus, the passengers hung flags saying "SAVE US" in Hebrew and English on both sides of the ship. The engine, which had been tried to be repaired for weeks, was still not working. Turkish authorities abandoned the ship to its fate, about 10 km from the Bosphorus, and Struma began to drift at sea.

The ship, which drifted throughout the night, sank after a huge explosion on the morning of February 24. As the Struma sank rapidly, many people drowned in their cabins. Many tried to stay afloat by holding on to wooden ship parts, but when no help came for hours, they either drowned or died as a result of hypothermia.

Although it was estimated that there were 768 people in the Struma disaster. Recently, according to the results of an examination of six different passenger lists a while ago, it was found that 781 refugees and 10 crew members, including more than 100 children, died. Only a 19-year-old passenger named David Stoliar and the chief mate named Ivanof Diko survived the explosion. Stoliar and Diko tried to survive by holding on to a piece of wood until the morning. The two was about to freeze at this time. Then, having lost all hope, Diko threw himself adrift and ended his life. When Stoliar was about to die, he was found by a Turkish rescue boat and brought ashore. Stoliar was subsequently detained for weeks. Simon Brod, one of the leaders of Istanbul Jews and a businessman who saved many Jewish refugees fleeing to Turkey in those years, ensured that food was brought to Stoliar during his two-month detention. When he was released and given a travel document by the British government to go to Palestine, he took him home and gave him clothes, a suitcase and a train ticket to Aleppo.

For many years, it was not known why the ship sank. In the light of documents released from the Soviet archives in the 1960s, it was understood that Struma was torpedoed and sunk by the Soviet submarine Ş-213. The same submarine sank the Turkish cargo ship Çankaya on the evening of February 23. At that time, the Soviet submarine was fulfilling a secret order to sink all neutral or enemy ships entering the Black Sea in order to prevent the flow of strategic supplies to the Nazi armies in the north of the Black Sea. The sinking of Struma was recorded in the Soviet military archives as follows:

On the morning of February 24, 1942, the Ş-213 submarine under the command of Lieutenant D. M. Denejko and Political Commissar A. G. Rodimatzav encountered the enemy ship Struma, which weighed 7 thousand tons and was unprotected. The torpedo fired from the submarine from a distance of 1118 meters hit its target and sank the ship. During the operation, Petty Officer Sergeant Major V. D. Chernov, platoon commander Sergeant G. G. Nusov and torpedo operator Private I. M. Filtov showed outstanding courage.